Most of us navigate the world using a simple linguistic tool: the personal pronoun. “I” am writing this; “you” are reading it. These words seem fundamental, almost universal, to how we define ourselves and interact with others. They clearly delineate the speaker and the listener, anchoring our individual perspectives in every conversation. But what if a language didn’t have direct, explicit words for “I” or “you” as we understand them?

This isn’t merely a hypothetical exercise. Across our diverse planet, there exist languages, spoken by millions, where such explicit first and second-person pronouns are either absent or very rarely used. This linguistic feature isn’t a deficiency; rather, it often reflects a profoundly different approach to communication, selfhood, and society. It challenges our common assumptions about how human beings frame their experiences and relate to their culture.

So, how does communication function without these seemingly indispensable words? Speakers in such languages still convey who is performing an action or to whom an action is directed, but they do so through a rich tapestry of context, verb conjugations, honorifics, and implicitly understood social roles. It’s not a matter of ambiguity, but rather a different kind of precision, one deeply embedded in shared understanding and interpersonal dynamics. For instance, instead of saying “I went to the market,” one might use a verb form that implies the speaker as the agent, or simply state “Went to the market,” with the context making the “who” perfectly clear.

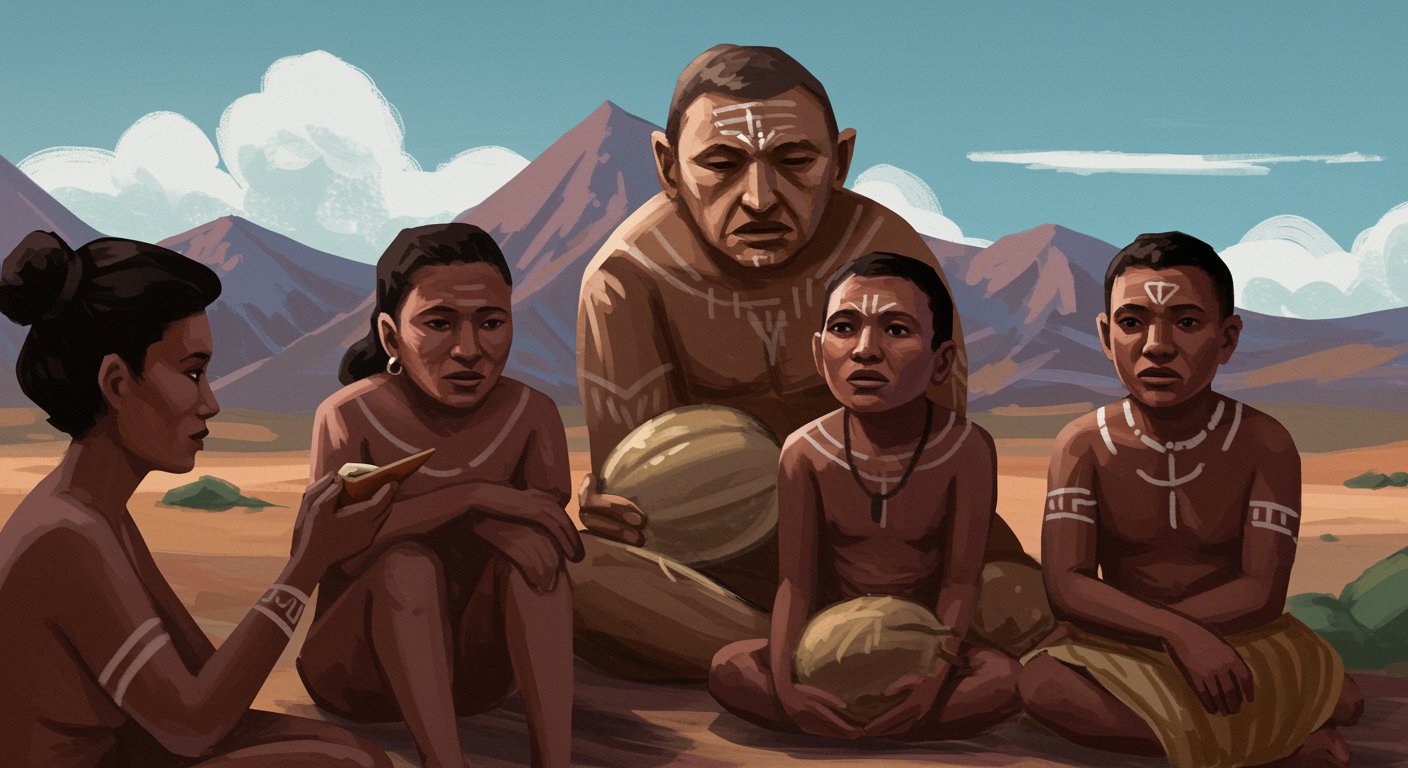

The ‘why’ behind this linguistic evolution often intertwines with a culture’s core values. Many societies that employ such language structures tend to prioritize group harmony, hierarchy, or the situation itself over the individual actor. The concept of the self is frequently understood not as an isolated entity, but in constant relation to others, to family, to community, and to one’s social standing. This perspective is a cornerstone of many long-standing traditions and social norms. In these contexts, constantly highlighting the individual “I” or directly addressing “you” might be considered unnecessary, or even rude, as it could disrupt the delicate balance of social interaction.

Consider Japanese, a language renowned for its complex politeness system. While words like watashi (I) and anata (you) exist, their direct use, especially anata, can often sound impersonal or even impolite. Speakers frequently drop explicit subjects altogether when the context is clear. Instead of “You like coffee?” one might ask “Coffee, like?” If an explicit subject is needed, a person’s name or title is typically preferred. The choice of word for “I” also varies greatly depending on the speaker’s gender, social status, and relationship to the listener – boku for a young male, ore for a very casual male speaker, watakushi for more formal settings. This nuanced usage underscores an emphasis on the relationship and situation over the individual pronoun.

Similarly, in Javanese, spoken on the island of Java in Indonesia, an elaborate system of speech levels dictates vocabulary and grammar based on the relative social status of the speakers. Referring to oneself or others involves a careful selection from different lexical sets (Ngoko, Krama, Krama Inggil), which can render direct, undifferentiated pronouns for “I” and “you” largely redundant or even inappropriate. A lower-status speaker would use one set of terms when addressing a higher-status individual, and vice-versa, with each choice implicitly signaling the speaker’s understanding of their place within the social hierarchy. This intricate system minimizes the need for explicit “I” and “you,” as the appropriate terms for referring to individuals are already baked into the formality level of the entire interaction.

These linguistic structures are not merely academic curiosities; they offer a profound window into how different cultures perceive and organize reality. The absence of a prominent, universally applicable “I” can subtly, yet powerfully, foster a less individualistic understanding of agency and responsibility within a society. It encourages a worldview where actions are often seen in collective terms, where the focus shifts from who did something to what was done, or how it affected the group. This deeply ingrained aspect of language highlights how words are not just labels for pre-existing thoughts, but active shapers of our cognitive landscape and our sense of self.

Ultimately, the study of languages without explicit “I” or “you” forces us to reconsider the fundamental building blocks of human communication and identity. It reminds us that our assumptions about how language works are often products of our own linguistic background. By observing these diverse ways of speaking, we gain a richer appreciation for the vast spectrum of social organization and the intricate dance between culture, tradition, and the very words we use to make sense of our world. These languages don’t just speak differently; they think differently, offering valuable insights into the flexibility and ingenuity of the human mind.