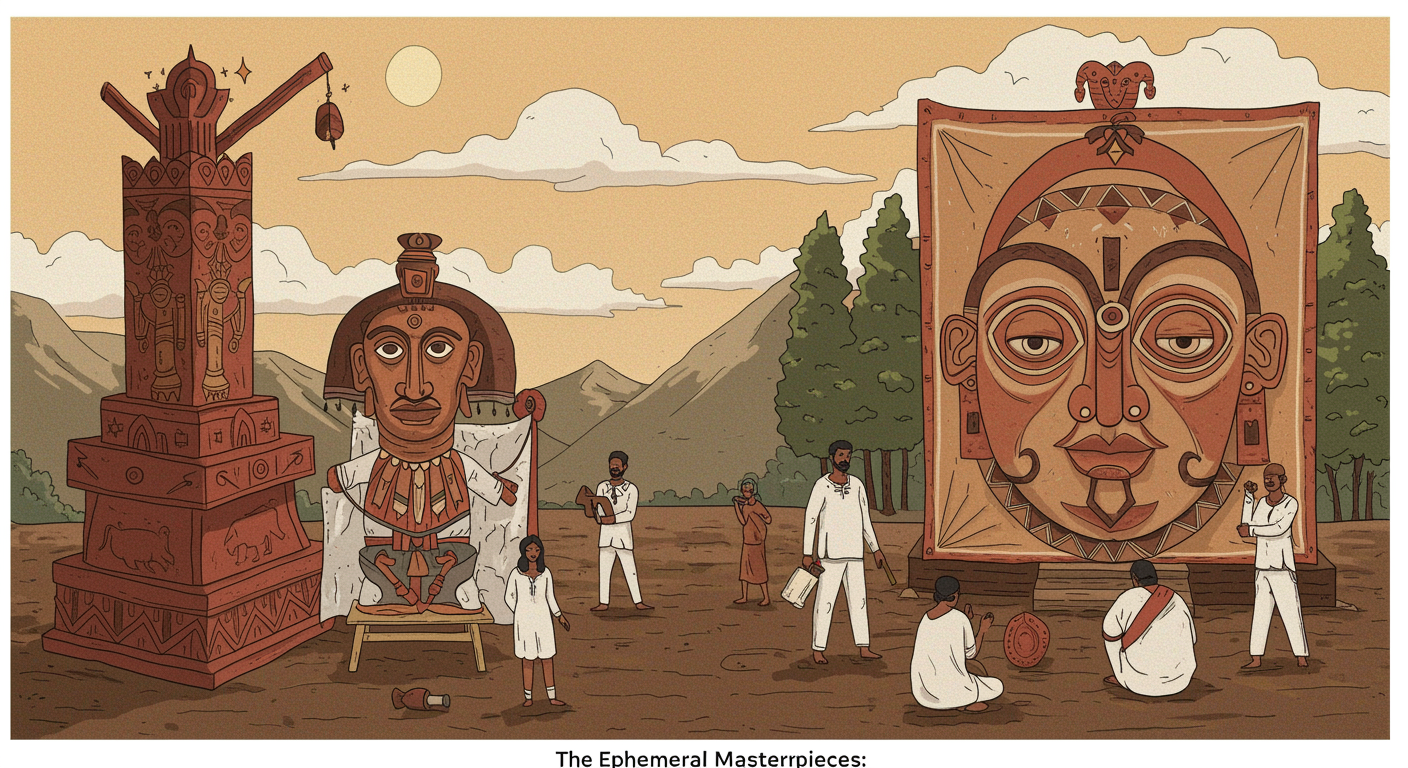

Imagine dedicating days, weeks, or even months to crafting an intricate, breathtaking work of art. You pour your skill, your focus, and perhaps even your spiritual energy into its creation, piece by delicate piece. Now, imagine that the culmination of this effort isn’t its display in a gallery or its preservation for future generations, but its deliberate dismantling or natural decay. This concept challenges a widely held notion that art should endure, yet it is a profound and ancient practice woven into the fabric of many human cultures worldwide.

For much of Western society, the value of art is often tied to its permanence, its ability to transcend time and speak across centuries. We build museums to house and protect masterpieces, striving to preserve every brushstroke and chisel mark. But what if the very act of creation, the communal effort, or the transient nature of existence itself is the true artistic statement? What if the destruction of the art is not an end, but an essential part of its meaning?

One of the most widely recognized examples of this ephemeral art tradition comes from Tibetan Buddhism: the creation and dissolution of the sand mandala. Monks meticulously construct these intricate cosmic diagrams using millions of grains of colored sand, sometimes working for days or weeks. Each grain is carefully placed to form symbolic patterns representing the universe, a specific deity, or a spiritual concept. The process is a meditative practice, a devotion to impermanence. The completed mandala, a vision of vibrant perfection, is then ceremonially swept away, often into a river or ocean. This act powerfully symbolizes the transient nature of life, the attachment to worldly things, and the continuous cycle of birth and death, echoing the Buddhist principle of detachment from samsara. The beauty is not in the object’s longevity, but in the practice, the focus, and the teaching it embodies.

Across the globe, other cultures embrace similar philosophies. In Bali, intricate offerings known as canang sari are a daily ritualistic art form. These small, beautiful baskets woven from palm leaves are filled with flowers, rice, cookies, salt, and sometimes money, representing gratitude and devotion to the Hindu deities. Every morning, Balinese people place these offerings at temples, homes, and even on the street, believing they nourish the spiritual realm. They are vibrant, colorful compositions, yet they are not meant to last. Exposed to the elements, they wither, decay, and are eventually replaced. The art lies not in the preserved object but in the constant, daily act of creation and offering, reinforcing the community’s spiritual connection and their harmonious relationship with the divine and the natural world. This tradition highlights a deeply social and spiritual aspect of their culture.

Similarly, among some Indigenous North American traditions, such as the Navajo (Diné), sand paintings are created for specific healing ceremonies. These sacred designs, often depicting deities or mythological events, are drawn on the ground using natural pigments like sand, cornmeal, and pollen. They are not merely pictures; they are potent sacred spaces intended to draw specific healing energies into a patient. The ill person sits on the painting, becoming one with the sacred imagery, absorbing its power. Once the healing ritual is complete, the sand painting is meticulously erased, often before sundown. The destruction is crucial; it releases the energy and disposes of the illness that has been absorbed into the painting, ensuring its power is used for its intended purpose and not misused. This process underscores the functional and ritualistic purpose of the art, where the outcome for the human recipient is paramount, not the art object itself.

These diverse cultural practices illuminate several profound insights into the human condition and the very nature of art. They teach us that the value of creation isn’t solely in its permanence or its ability to be collected and displayed. Sometimes, the true worth lies in the process of creation itself—the collective effort, the shared spiritual experience, the meditation, the focus, and the community engagement. The act of making something beautiful and then letting it go fosters humility, detachment, and an understanding of impermanence, which is a fundamental aspect of existence. Furthermore, it emphasizes the cyclical nature of life, death, and renewal, reflecting patterns observed in the natural world. For these societies, the temporary nature of the art is not a flaw, but an inherent, celebrated characteristic that deepens its meaning and its role within their social and spiritual lives.

These traditions challenge us to reconsider our own definitions of art, value, and legacy. They demonstrate that art can be a powerful tool for spiritual practice, community building, and conveying deep philosophical truths, even if its physical form is fleeting. The true enduring legacy of these ephemeral masterpieces might not be found in an artifact on display, but in the spiritual insights they impart, the cultural bonds they strengthen, and the profound lessons they offer about our place in the ever-changing tapestry of life.